What is JIT (just-in-time) compiler?

this post is part of my learning journey to understand compiler and compiler architecture. I’m not an expert in compiler, so if you find any mistake, please let me know.

What is JIT (just in time compiler)

I kinda know what a compiler does, but didn’t get what “just in time” means and why it is important. So I decided to dive deeper into it.

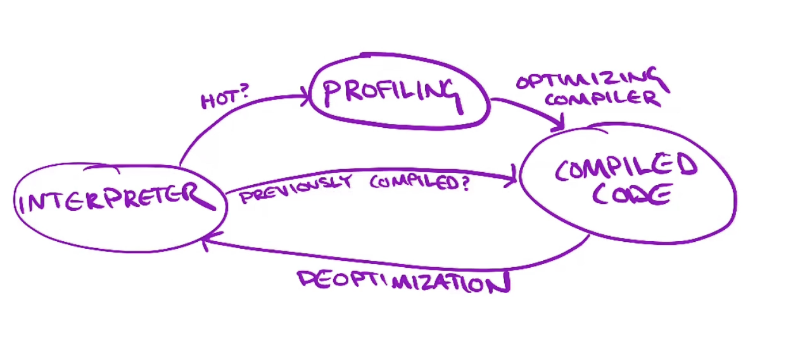

(diagram from lecture)

(diagram from lecture)

JIT (just-in-time compiler) can be described as dynamic code generation or dynamic compilation. Compared to static compilation that purely compiles without any knowledge of runtime, with JIT, the compiler can get knowledge of runtime information, which can be used for optimized execution. This is impossible with AOT (ahead-of-time), static compilation because the compile stage and execution stage are totally separate.

For that reason, many modern languages are mixing this compile stage with the execution stage by using JIT methods to get the most optimized performance. Dynamic languages like javascript and python are benefiting from faster interpretation based on optimized feedback from compile stages.

JIT compiler had been implemented with various runtimes such as JVM(Java), Erlang VM, Android Runtime and blockchain runtimes such as EVM, Cairo and more. Or it could be designed like Julia, which behaves like an AOT compiler.

The most popular approach is known as method JIT, which uses a function as a unit. During execution, by observing the frequency of function calls heuristically, it determines the optimization level (e.g., cold, hot). Usually, “hot” means it has been executed frequently, so it’s targeted to be optimized using JIT. There is another approach based on execution trace, called tracing JIT. Throughout the control flow graph, you extract the “hot” path from traces that were actually executed.

Tiny JIT implementation

So I implemented a super naive approach to simply get a grasp of how it works. Check out full code.

- Interpreter : Just executes the instructions and while running, it profiles to observe if a function is hot. And it detects if a function has already been JIT compiled, executing native machine code instead of interpreting instructions.

- Profiling : Uses

execution_countto track the execution time of functions. So simply if a function gets executed 10 times, it turns the interpreter into JIT compile mode. - JIT compile : From given instructions, generates native machine code and caches the pointer for further execution.

mmap

To implement JIT, I had to alter the memory segment to compiled machine code and later execute this code. A common way to implement this is to use the mmap unix system call, which creates a new mapping in the virtual address space of the calling process.

One interesting thing I found was that compared to the original Unix syscall, my machine (M2 Mac, ARM64) syscall supports the MAP_JIT flag that creates memory that’s both writable and executable in a hardened environment.

jit_compile in Interpreter

So here’s a simple jit_compile method of Interpreter. There are two parts: 1) hand-written machine code generation and 2) JIT mechanics that involve write/execute. The opcode used here is ADD(immediate).

Regarding JIT mechanics, I got the idea from this tutorial, but on Mac, it returned a permission error mmap failed: Permission denied (os error 13). So I first gave write permission to the virtual address space, and then copied the machine code to the permissioned space using the memcopy syscall(= copy_nonoverlapping). And last, with mprotect syscall , I provided execution permission to the new address space to run machine code in further execution.

fn jit_compile(&self, pc: usize) -> (*mut u8, usize) {

// 1) generate machine code (ARM64)

let (machine_code, code_len) = match &self.code[pc] {

Instruction::Add(x, y) => {

let mut code = vec![

0x20, 0x00, 0x00, 0x8B, // ADD X0, X0, X1

0x00, 0x04, 0x00, 0x91, // ADD X0, X0, #1 (placeholder for x)

0x00, 0x08, 0x00, 0x91, // ADD X0, X0, #2 (placeholder for y)

0xC0, 0x03, 0x5F, 0xD6, // RET

];

// Encode immediate values (12-bit, shifted left by 10)

let imm_x = ((*x as u32) & 0xFFF) << 10;

let imm_y = ((*y as u32) & 0xFFF) << 10;

code[4..8].copy_from_slice(&(0x91000000 | imm_x).to_le_bytes());

code[8..12].copy_from_slice(&(0x91000000 | imm_y).to_le_bytes());

(code, 16)

}

};

let alloc_size = PAGE_SIZE;

// 2) JIT mechanics

unsafe {

let ptr = mmap(

std::ptr::null_mut(),

alloc_size,

PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANON,

-1,

0,

) as *mut u8;

if ptr == libc::MAP_FAILED as *mut u8 {

panic!("mmap failed: {}", std::io::Error::last_os_error());

}

std::ptr::copy_nonoverlapping(machine_code.as_ptr(), ptr, code_len);

// Now make the memory executable

if mprotect(ptr as *mut libc::c_void, alloc_size, PROT_EXEC) != 0 {

panic!("mprotect failed: {}", std::io::Error::last_os_error());

}

println!("Memory protection changed successfully");

(ptr, alloc_size)

}

}

LLVM

As we take a look at simple JIT compilation, it is indeed not optimal to turn raw machine code by hand. Why? 1) It is pretty unsafe as the compiler has permission to write and execute directly – which could lead to malware. 2) For complex programs – not just addition like our example – it’s quite inefficient to run hand-written machine code.

So instead of turning our hot function into raw machine code, we can turn it into LLVM IR and let LLVM handle our IR to machine code. This abstracts away many of the low-level details that allow us to focus on higher-level optimizations and language features.

Also, another cool compiler backend cranelift is worth checking out.

// Direct Machine Code Generation (simplified)

fn generate_add(x: i32, y: i32) -> Vec<u8> {

let mut code = vec![

0x20, 0x00, 0x00, 0x8B, // ADD X0, X0, X1

0x00, 0x04, 0x00, 0x91, // ADD X0, X0, #imm (x)

0x00, 0x08, 0x00, 0x91, // ADD X0, X0, #imm (y)

0xC0, 0x03, 0x5F, 0xD6, // RET

];

// Complex encoding logic here...

code

}

// LLVM IR Generation (pseudo-code)

fn generate_add_llvm(x: i32, y: i32) -> String {

format!("

define i32 @add(i32 %a, i32 %b) {{

%sum1 = add i32 %a, %b

%sum2 = add i32 %sum1, {}

%result = add i32 %sum2, {}

ret i32 %result

}}

", x, y)

}

Downside of JIT

Yes, JIT is cool but it is not perfect. As the example above, for simple addition, it is not worth to use JIT.

Iteration 8

Result: 307, Time: 500ns

Iteration 9

Result: 307, Time: 500ns

Iteration 10

JIT compiling instruction at pc 0

Machine code: [20, 00, 00, 8B, 00, 0C, 00, 91, 00, 10, 00, 91, C0, 03, 5F, D6]

Memory protection changed successfully

Result: 307, Time: 11.875µs

Iteration 11

Executing JIT compiled code at pc 0

Result: 307, Time: 4.375µs

Iteration 12

Executing JIT compiled code at pc 0

The time of executing JIT mechanics is 11.875µs, but the time of executing JIT compiled code is 4.375µs where in contrast(without JIT) is 500ns. For simple project, simple operation JIT can be just over engineering.

Security can also be another problem. As it involves sophisticated code generation and execution throughout the runtime, there could be exploits if implemented improperly. Check out this blog for example.

Further reading

-

CS 6120: Lesson 11: Dynamic Compilers from Adrian Sampson really helped me on understanding spectrum of compiler/interpreter.

-

This basic tutorials about JIT helped alot on understanding.

-

There is some discussion around AOT vs JIT, Angular: Is AOT Worth It?, aot_vs_jit_comilation probably more.

And some other resources that i found interesting while researching

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/understanding-jit-aot-compilation-dart-marwa-aldaya-tnycf/

- https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/sdk-java-technology/8?topic=reference-jit-compiler

- https://kobzol.github.io/rust/rustc/2024/03/15/rustc-what-takes-so-long.html

- https://ucarion.com/llvm-rust-toy-compiler

- https://www.cs.cornell.edu/courses/cs6120/2020fa/self-guided/

- https://wolchok.org/posts/how-to-read-arm64-assembly-language/

- https://mcyoung.xyz/2023/08/01/llvm-ir/

- https://webkit.org/blog/3362/introducing-the-webkit-ftl-jit/